88th REGIMENT OF FOOT, THE CONNAUGHT RANGERS

CRIMEAN PENINSULA 1854

Control of the keys of the church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, was the spark that ignited the Crimean War 1854-1856. Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholic monks argued over control of all the Christian relics and sites in the Holy Land. These arguments were often heated and fist fights were common. In Bethlehem, the violence reached a new level resulting in the deaths of several Orthodox monks. Czar Nicholas of Russia, used this opportunity to pressurise the Ottoman Empire to grant Russia the protectorate of the Christians and the Holy sites. Nicholas viewed the Ottomans as “the sick man of Europe” and would have little choice but to agree. The Sultan refused Russia’s demands. In response, Russia mobilised its army and seized control of the Orthodox Ottoman territories of Moldavia and Wallachia. The Ottoman Sultan’s plea for help was answered by France and Britain, who were suspicious of Russia’s expansionism in the near east. The Russian Empire was a prisoner of its geography, it had no warm water port. All the Baltic and White Sea ports froze over in winter denying access to the Atlantic. Petropavlovsk on the Pacific had no lines of communications and had little use in projecting Russian power. The Black Sea fleet was easily confined by restricting access through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelle Straits. Control of Constantinople, the birthplace of the Orthodox Church, was the key to unlocking the Black Sea fleet.

Britain and Russia had an ongoing strategic rivalry from the early 19th century (The Great Game). At the heart of the difficulty was the Indian sub-continent. It was the jewel in the crown of the British Empire. India accounted for one third of all economic output and contributed over a third of all revenue going to the Treasury. Russia’s push southwards in Asia threatened control of India.

This geopolitical game was played out in the countries that separated both empires. The balance of power in Europe had to be maintained and Russia’s march south stopped. Napoleon III provoked the war, his motivation being different to Britain. He had just seized power and declared himself Emperor of France. He was unable to go forward for election for another term as President, as the constitution prohibited it. He wanted to step out from under the long shadow cast by his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte, and gain the respect of his country, Europe and the wider world. He believed this could only be achieved by winning a decisive large scale land war, against a major European power. This would copper fasten his legacy and reassert France as the foremost European power.

In February 1854, the 88th Connaught Rangers were stationed in Bury, Burnley and Ashton-under-Lyne in England. The unit was selected to form part of an expeditionary force to be deployed to the near east. Lt. Col Shirley was appointed Commanding Officer. During the middle of March, the regiment moved to Fulwood Barracks where training, equipping and organisation of companies could be undertaken prior to deployment. The Rangers received orders that on 4 April they were to depart at Liverpool docks on board the Cunard steamer Niagara. The Marching out State records the regiment strength as 32 Officers, 39 Sergeants, 20 Band, 10 Drummers and 810 Rank & File, total 911, alongside women allowed to accompany their husbands. On the night before leaving, there were 150 men absent from barracks at tattoo hrs (23:59). These absentees all reported for duty the following morning. All were present when the Regiment embarked. Before leaving Lt. Col Shirley addressed the men:

“that he never felt prouder in his life. Not a man absent from embarkation; and that he hoped we should add three or four more jaw-breaking names to the engagements placed on our colours, feeling confident that the Rangers of the present day would prove equal to the Rangers of the Peninsular War.”

The march to the docks was made difficult by the enthusiastic cheering crowds who turned out to support the men and wish them well. They set sail at three in the morning, destination Scutari, Turkey, opposite Constantinople. The voyage was calm an uneventful with a short stopover in Malta to take on coal. They arrived on 19 April and took up quarters in a large Turkish military barracks. This barracks in Scutari would be converted to a hospital during the war, later made famous by Florence Nightingale who arrived there in November 1854, with 28 British nurses.

It would be a war like no other before. The development and introduction of a new rifled musket, the 1851 Pattern Minie Rifle, outclassed the Russian smoothbore musket, and had an effective range of up to 400 yards and higher accuracy rate of 48%. Stated in a book by General Todleben Defence de Sevastopol (1865) “when fired in volleys at 800 yards caused such loss among the gunners that it was more effective than shrapnel in silencing the Russian artillery.” This was a big advantage in an infantry firefight and shifted the balance in the French and British favour. Steam powered iron clad ships, exploding shells and sea mines all required a new tactical approach from the Admiralty. Telegraph, submersible cable and the embedded news correspondents, the most famous being an Irishman, William Howard Russell of The Times, brought the war home in articles he penned:

“A large number of sick and, I fear, dying men were sent into Balaklava today on French mule litters and a few of our bat horses. They formed one of the most ghastly processions that ever a poet imagined. Many of these men were all but dead. With closed eyes, open mouths, and ghastly attenuated faces, they were borne along two and two, the thin stream of breath, visible in the frosty air, alone showing they were still alive. One figure was a horror-a corpse, stone-dead, strapped upright in its seat, its legs hanging stiffly down, the eyes staring wide open the teeth set on the protruding tongue, the head and body nodding with frightful mockery of life at each stride of the mule over the broken road”. (The Times, January 23 1855).

His reports told the unvarnished truth of suffering endured by the soldiers. They died of cold, hunger, exposure and lack of medical care. The incompetence of the military leadership in his reports, destroyed the reputations of Lords Raglan and Cardigan. Russell exposed the total incompetence, ineptitude, corruption and unnecessary bureaucracy of the Commissariat Department (Supply Department) which led to public outrage and the eventual collapse of Lord Aberdeen’s government in 1855.

Telegraph and steam power opened a line of communication between the newspaper and war correspondents. Filing of stories that took two to three weeks at the start of the war, were by the end, measured in hours. Reports were eagerly awaited by the public who were engrossed with news from the front. Russell’s reports inspired Florence Nightingale to travel to Scutari hospital where she developed sanitary techniques and effective administration and management of the disease-ridden hospitals. His report on the Charge of the Light Brigade at the battle of Balaclava moved Alfred Lord Tennyson, the Poet Laureate, to write his famous poem of the same name in 1854.

However, not all were admirers of Russell’s work. Prince Albert stated, “the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country”. Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed sensitive military information in his reports. By the latter stages of the war, censorship was imposed. The era of press freedom was over.

The Rangers stay in Scutari would be brief. They were redirected to Varna in support of Omar Pasha’s Ottoman Army, who had halted the Russian advance at the fortress of Silistria. At this time, Tsar Nicholas was aware of the mobilisation of the Austrian Army, a former ally, along the borders of Moldavia and Wallachia. Fearing war with another European power, Russia lifted the siege of Silistria and retreated behind the Russian borders. Russia had now met the conditions laid down to avoid war with the Allies. London and Paris wanted to punish Russia for their escapade in the Balkans. New orders were issued instructing the Allied armies to invade the Crimean Peninsula, sink or capture the Russian Black Sea fleet and lay ruins to the dry docks and naval base in Sevastopol. News of the move was greeted with relief. Varna had

inflicted a heavy toll on the Rangers. On Sunday, 23 July, cholera made its first appearance. Sergeant Dempsey, a healthy young man, was the first to succumb to the disease. By 5 September, in less than two months, the Regiment had lost 49 men to cholera and 51 to fever. The Rangers were a shadow of the unit that left Liverpool five months earlier. Weakened, they boarded the sailing vessel Orient en route to the Crimean Peninsula, with a total of 27 Officers, 774 Rank and File and 16 women.

The aptly named Calamita Bay, 25 miles north of Sevastopol, was to be the staging ground for the invasion force. As there was no port available, men, equipment and animals had to be rowed ashore. It took all of four days to complete this mammoth task. During the landing the men were at their most vulnerable. Prince Menshikof, with 37,0000 Russian soldiers under his command, decided not to contest the landings but instead concentrated his army to the cliffs on the south bank of the river Alma.

The Rangers were one of the first units to step foot on Russian soil. Securing the landing ground as part of the Light Division and their objective was to advance a few miles inland.

It was here they settled for the night, albeit in very bleak conditions. Every man carried a blanket, a spare pair of boots and a three day ration of salt pork. Cooking was virtually impossible with no fuel available apart from grass. Lt. Col, Steevens writes “this is our first experience of lying down to sleep in the open air can never be forgotten.” There were torrential downpours and extreme cold and every man was saturated to the bone. It was here on that night they lost their first men on Russian soil. Pte John Duncan and Pte Thomas Burke died of cholera. However, the following day was very warm which allowed uniforms to dry whilst on the march.

Before noon, on the 20 September, the advancing army made visual contact with their adversaries. The stage was now set for the first major land battle since Waterloo in 1815. The enemy were at an advantage, perched on high ground on the southern bank of the river Alma. This provided a strong defensive position. However, Prince Menshikov was an over confident and incompetent military commander. He failed to properly plan and put little effort in to constructing appropriate defensive fortifications. So arrogant was he, local gentry from Sebastopol were invited to view the battle, whilst sipping on champagne that he provided!

The Rangers, being part of the Light Division, were in the vanguard for the battle of the Alma. They were first to cross the knee deep river and took up their positions on the northern bank. They awaited orders to advance. They moved at pace under heavy fire. General Buller ordered the formation of a defensive square as he perceived an imminent cavalry attack. This attack never materialised resulting in the Rangers losing their place in the line of attack. Only the Grenadier Company of the Rangers advanced, into a hail of heavy fire and grapeshot. They cheered as they ascended the heights of the Alma and managed to push the Russians back, forcing them into a hasty retreat. The battle was over by 3pm. Afterwards, Lord Raglan rode through the ranks to jubilant cheers. The colours of the 88th were uncased and proudly exposed to view. However, Lord Raglan, relying heavily on General Sir Burgoyne, officer in command of the engineers, whom he served alongside with during the Peninsula War and Waterloo, made a fatal judgement error, by failing to seize the initiative and take advantage of the chaos in the confused Russian ranks. His indecisiveness cost the lives of thousands of soldiers and condemned the army to the harsh grinding Russian winter. Raglan was a brave officer who fought with distinction during the Peninsula War and lost an arm at Waterloo. All his career he was a staff officer, never having to make tactical decisions, only implement them. General Sir John Burgoyne believed the only way to take a fortified position was to lay siege and pound it into submission. The decision was made. Siege works would begin on the southern side of Sevastopol, and Balaclava, five miles to the south, the headquarters and the port that would supply the army.

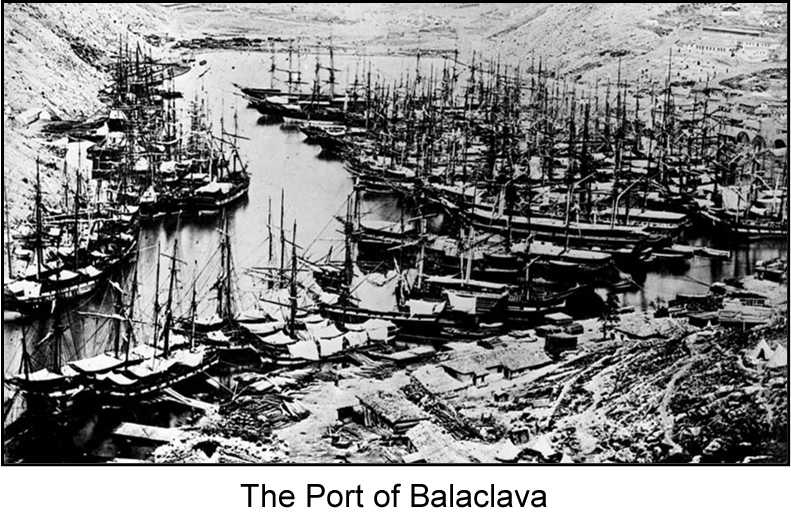

The port of Balaclava was a narrow inlet with limited capacity to support any military operation.

The Russian army would soon counter attack. Their objective was to cut the line of communication between the port of Balaclava and the siege army in Sevastopol, depriving them of much needed resources. The attack came on 25 October. The Rangers were not involved directly in this battle apart from a few sick convalescing men who were part of the invalid depot. One hundred of these men, from several regiments, were put under the command of Capt. E.H. Maxwell of the 88th.

They took their positions on the left hand side of the 93rd Highlanders and formed a part of the defence of Balaclava. It was reported by Russell in his despatch to The Times of 14 November 1854, that “a thin red streak topped with a line of steel” is all that stood between success or defeat. The line held and repulsed the Russian cavalry. Balaclava is famed for the Charge of the Light Brigade and the commonly used phrase ‘the thin red line’ as mentioned in Russell’s dispatch.

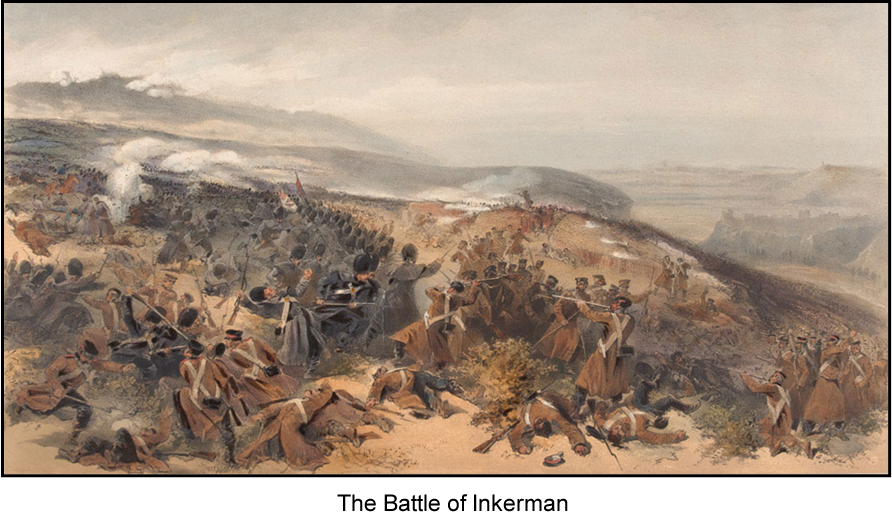

The next Russian onslaught, the battle of Inkerman, the Rangers would play a pivotal role. On the morning of the 5 November 1854, a force of 35,000 Russians launched an attack on the allied army. It was a misty start to the day, covered in a dense blanket of fog. The Rangers, on morning parade before daylight, were detailed for trench duty. Four companies of the 88th were dispatched to the front. All the while, others who were preparing breakfast after their return from night duty in the trenches heard the sound of gun fire in the distance. They were ordered to advance immediately in the direction of the fire without any food or adequate supply of ammunition. An account by Col Steevens stated that “It is worthy to record, that the four companies of the 88th Regiment were the first of the reinforcements from camp to reach the field of action, where, for several hours they sustained, unsupported, a trying conflict with the Russians”.

With dense fog and the accuracy and range of the Minie Rifle, the Russian army were unaware of the allies desperate situation and overestimated their strength, which lead to them failing to take advantage of their numerical superiority.

In search for reinforcements and a fresh supply of ammunition, Major Maxwell rode out seeking aid. He encountered General Pennefather, in overall command of the battle and relayed to him the catastrophic predicament the Rangers were in. Pennefather replied “I do not know where to find a man or a round. The 88th must stand their ground, give the Russian’s the bayonet, or be driven into the sea”. Meanwhile back in camp, Quartermaster Moore, a very experienced soldier, upon hearing the prolonged firing, realised the Rangers were very low in ammunition. He loaded bat ponies and courageously made his way to the front. He arrived not a minute too soon as nearly every round was expended. As the fog lifted, British and French reinforcements arrived and drove the Russian Imperial Army into a hasty retreat. The Battle of Inkerman broke the will of the Russians. No longer were they confident to engage the allies on open ground. The war would now enter a new phase, mirroring scenes from the Western Front in 1916.

On the 14 November, just over a week after Inkerman, the troops were introduced to the infamous Russian winter by a ferocious storm, which left them fully exposed as they camped on high open ground. Almost all tents were blown down exposing the men to an insuperable deluge of sleet and rain. The port of Balaclava offered poor protection, wreaking havoc on vessels and destroying invaluable cargo. Due to port congestion, supply ships lay anchored off shore. A total of 21 ships were destroyed, carrying with them essential supplies of winter clothing, tents and ammunition. Tsar Nicholas boasted of unleashing his best two generals, ‘January and February’, and offered the allied troops free transport home.

The delay in attacking Sevastopol provided the Russians invaluable time to fortify the unprotected south side of the city. Over 500 guns, fortified redans and several lines of earth works were constructed making it a formidable barricade. The Russian Navy scuttled their prized Black Sea fleet at the mouth of the harbour, preventing any entry by other vessels into the shallow inlet, thus neutralising the threat posed by the Royal Navy. This would set the stage for an eleven month siege.

This siege provided extremely poor working conditions for the allies. The supply chain (The Commissariat) broke down completely. Hunger was a daily experience for the troops. After spending a night in freezing conditions in the trenches, soldiers were then ordered to trek the seven miles to Balaclava in order to collect the following day’s rations of salt pork and biscuits. The combination of unsuitable clothing, poor diet, harsh weather and fatigue left even the strongest men exhausted. It is true to state some men were literally worked to death. Others died of starvation. More froze to death. Extreme exhaustion left others vulnerable due to sleep deprivation which led to them being bayoneted to death whilst falling asleep on duty in the trenches.

Sniper fire, random artillery shelling and trench raids were a regular occurrence. On 14 April, a young Lt. Preston was killed by sniper fire. His loss was deeply regretted by the 88th. He was only 16yrs old. His name is recorded on the memorial plaque in St. Nicholas’s Collegiate Church in Galway city.

“The misery of this winter passes all description, or even conception, by anyone who did not experience it. It is difficult to record the noble patience, the enduring perseverance, the ready courage, the willing submission to discipline and order, of the men of the regiment, without using expressions which might seem exaggerated to those who did not witness it. No words can, however, do justice to their conduct. It was beyond all praise” (Digest of Services).

Given the dire circumstances the allies found themselves in, an urgent technological solution was required. A light gauge railway was constructed in record time connecting Balaclava with Sevastopol. It was supervised under the watchful eye of James Beatty, an Irish railway engineer. This allowed for the transportation of flat pack huts, flat pack field hospitals, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, provisions and heavy artillery that would pound Sevastopol into submission. Completed by the end of March it was too late for the winter of 1854/55. However, it did ease the hardship previously endured.

A synchronised artillery bombardment on the 8 September, which coincided with a French attack on the Malakhov bastion at 12 sharp, signalled a breakthrough in the siege. Within minutes the French tricolour was flying from the Malakhov tower. The British attempted to take the great Redan. This attack would see them stare death in the face. Like previous attempts, it ended in total failure, leaving the battlefield in a sea of blood, strewn with their dead and dying comrades.

The Russians, knowing of their dire situation, evacuated the city under the cover of darkness, using a hastily constructed pontoon bridge to the north of the harbour. Their capitulation was signalled by the sounds of large explosions as all remaining stores were destroyed. The costly eleven month siege was finally over. After the Paris Peace Treaty was signed on the 30 March, 1856, the Rangers soon afterwards departed for home. At 6am, on 9 June they were lead from the camp in Sevastopol, to HMS Belleisle in Kazatsh, by the combined bands of various regiments, and embarked for England. With a deep sense of loss, the men left behind 476 of their comrades, whom were killed in action or perished from disease. Brigadier General Shirley addressing the Rangers for the final time before handing over command of the Regiment to Lt. Col Maxwell said:

“The old soldiers will recollect that I felt confident that the Rangers of the present day

would prove equal to the Rangers of the Peninsula, and most nobly have they answered my expectations”

H Shirley Brigadier General.